Understanding Java Memory Model

These are notes taken to better understand the Java Memory Model, which I now publish as a blog post.

Programming language memory models, such as the Java Memory Model, attempt to define the behavior of multi-threaded programs. These specifications help to reason about code execution in a concurrent environment, even when the code runs on different hardware architectures or undergoes numerous compiler optimizations.

For example, given the following multi-threaded program:

| Thread I | Thread II |

|---|---|

|

|

Initially, all variables are set to zero, and each thread runs in its own processor. Can we reason about the output of the program?

It appears that the output depends on the hardware and compiler optimizations. On x86 architecture, the assembly version of this code will always print 1. However, on ARM architecture, it may print 0. Additionally, compiler optimizations can cause this program to either print zero or enter an infinite loop.

As a programmer, it would be frustrating if programs don’t work on new hardware (mobile devices, cloud servers) or with new compilers. Thus, high-level programming language memory models are defined to provide a set of guarantees that programmers, while writing code in that language, can rely upon.

But first, let’s understand what guarantees are provided by the hardware.

Hardware Guarantees

Let us imagine we are writing an assembly code for our multiprocessor computer. What kind of guarantees could we expect from the hardware?

Sequential Consistency

From Leslie Lamport’s 1979 paper:

The customary approach to designing and proving the correctness of multiprocess algorithms for such a computer assumes that the following condition is satisfied: the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program. A multiprocessor satisfying this condition will be called sequentially consistent.

This definition is natural to a programmer. It states that operations will be executed in the order they appear in a written program, and threads will be interleaved in some order.

For example, given the following program with two threads:

| Thread I | Thread II |

|---|---|

|

|

We could expect the following six outcomes from the above program in a sequentially consistent hardware, with interleaving of each thread operations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

As you can see, in the sequential consistent model the execution result where r1 = 1, r2 = 0 is not possible.

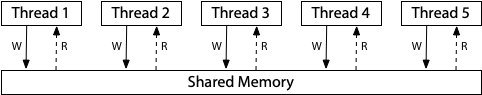

We can envision this model where all processors are directly linked to a single shared memory. In this case, there are no caches involved each write or read operation goes straight to the memory.

As we’ll see, modern hardware designs often give up on strict sequential consistency for performance reasons.

x86 Total Store Order (TSO)

The modern x86 architecture memory model is based on the following hardware structure.

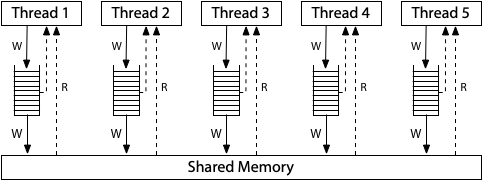

In this model, each write is queued in first-in, first-out (FIFO) order before being written to the shared memory. Similarly, each read first checks the local queue and then queries the shared memory. The local queue is flushed to the shared memory in FIFO order, ensuring that each write is applied in the same execution order in the processor.

This results in total store order (TSO). Once write reaches the shared memory, each next read sees it until it’s overwritten or buffered in the local write queue.

ARM Relaxed Memory Order

ARM processors have weaker memory models.

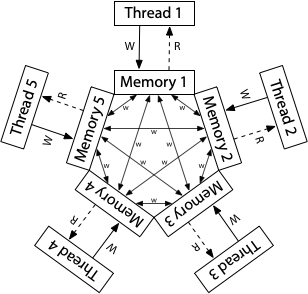

As depicted in the picture, each processor has its own copy of memory. Each write propagates independently to other processors and there is a possibility of write reordering. Additionally, a read can be delayed until it’s needed or until after a write.

In ARM hardware model, there is no total store order. It only provides total order for writes on a single memory location (coherence) that we will see later.

Data Race Free Sequential Consistency (DRF-SC)

In their 1990 paper called Weak Ordering — A New Definition, Sarita Adve and Mark Hill introduced a synchronization model known as the data-race-free (DRF) model.

This model assumes that there are distinct hardware memory synchronization operations, and memory read or write operations can be rearranged between these synchronization operations. However, reads and writes must not be moved across the synchronization operations.

A program is considered data-race-free if any two accesses to the same memory location from two different threads are either both read operations or are separated by a synchronization operation that forces one to happen before the other.

Well, this provides an agreement between hardware and software, given a data-race-free program, the hardware will execute it in a sequentially consistent manner. The above paper provides a proof, even for weaker ARM hardware, that the hardware will appear sequentially consistent to a data-race-free programs. This guarantee is abbreviated as Data Race Free Sequential Consistency (DRF-SC).

So far, we have been assuming that we are programming in an assembly language that is close to the hardware. Let’s now examine the guarantees offered by high-level programming language, Java’s memory model.

Java Memory Model

In the preceding section, we learned that if a programming language offers synchronization mechanisms to coordinate different threads, we can use these to create data-race-free (DRF) programs. Data-race-free multi-threaded program operations could be arbitrarily interleaved, and the outcome of this program can be explained by some sequential consistent execution, as if the operations are run on a single processor.

Java offers various options for synchronization mechanisms to develop DRF programs. It’s crucial to understand that these are “synchronizing instructions” which establish a happens-before relationship between code executed on one thread and code executed on another.

The main Java synchronization operations are:

- The creation of a thread happens before the first action in the thread.

- Unlock of mutex m happens before any following lock of m.

- Write to volatile variable v happens before any following read of v.

Of course, there are more synchronization operations in Java, but in this blog

we will focus on `volatile` since it demonstrates the main idea.

Happens Before

Java Memory Model (JMM) specifies which outcomes are permitted by the Java language. The outcomes are results of executions containing different orderings of operations of entire program.

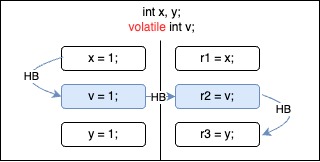

We could arrange all operations, including lock, unlock, volatile write, and volatile read, in some interleaving order. Then, as an example, we could write to a volatile variable v and subsequently later in the ordering read v, which observes that write. This creates a happens-before edge on that particular execution.

These edges define whether an execution has a data race; if there is no data race, then the execution behaves in a sequentially consistent manner.

This conforms to the definition of DRF-SC.

Two events occurring on separate processors and not ordered by the

happens-before relationship may happen at the same moment; the exact order is

unclear. We refer to them as executing concurrently. A data race occurs when a

write to a variable executes concurrently with a read or another write of the

same variable.

We should remark two important points:

- The happens-before edges also synchronize the rest of programs, ordering ordinary operations across threads.

- The happens-before edges are not established by locking or unlocking different mutexes, or accessing different volatile variables.

Compiler Optimizations

These JMM rules define which optmizations are allowed by the compilers.

Given the following program with two threads, which instruction reorderings are allowed?

These two orderings are allowed.

|

|

|---|

Write on y could be moved before write on volatile v since it doesn’t break happens-before (HB) edge and read on y can observe write on y with race.

Similarly, read on x could be moved after read on volatile v since it could observe result of write on x with race.

These two orderings are not allowed.

|

|

|---|

Both of these orderings break the happens-before edge.

For the first case, implementations cannot know if there is any read on x that should observe write on x before moving. Similarly, in the second case, implementations are unable to determine if the moved read on y should observe any preceding write to y.

Litmus Tests

In this section, we are going to run several litmus tests to evaluate how different models behave. These tests provide an answer to the question if certain outcome is possible or not under specific model.

In these examples, we assume that each shared variable starts with zero and each thread runs in its own dedicated processor. The rN is a thread-local variable, and we check if a thread-local result is possible at the end of execution.

Message Passing

Can this program see the following result r1 = 1, r2 = 0?

| Thread I | Thread II |

|---|---|

|

|

|

- On sequentially consistent hardware: no - On x86-TSO: no - On ARM: yes - Java language (plain): yes - Java language (volatile y): no |

|

This outcome isn’t possible in a sequentially consistent hardware model. We can imagine that each processor is directly connected to the shared memory, there are no caches, registers, or write buffers. Thus, if we see an update on x, then we should also see the update on y.

Similar reasoning applies to the x86-TSO model. The write buffer from a single processor is flushed in FIFO order, ensuring that the update on x should become visible if the update on y happens.

Please be aware that we are writing these programs in assembly like language, where each instruction is executed by the processor. For the ARM model, these instructions can be reordered. Writes can be run in a different order, resulting in the possibility of an outcome.

For the Java language, using plain variables, the outcome mentioned above is possible. The optimizing compilers can reorder updates on the x and y variables.

However, if we declare y as volatile, then write and read on a volatile variable produces a happens-before edge. This edge precludes the optimizing Java compiler from moving the update on x after write on y operation.

By making variable y volatile, the above outcome is not possible. Similar to x86-TSO, update on a volatile propagates all updates, including ordinary variables, before it into the memory. If read on y results in 1, then read on x must also result in 1.

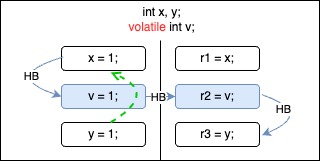

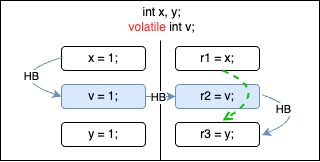

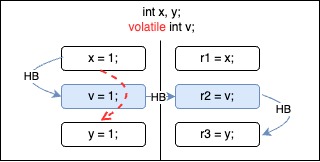

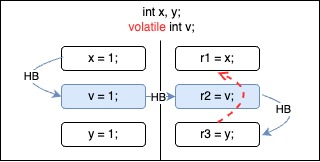

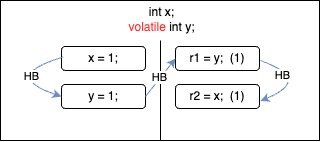

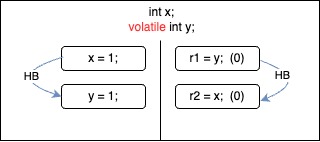

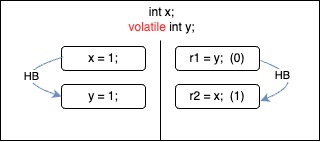

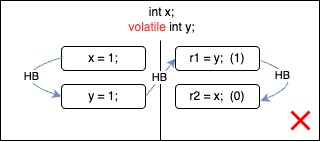

Message Passing Test — Happens Before Edges

We could easily visualize the happens-before (HB) edges in the possible executions of the message passing test.

|

|

|---|---|

| HB consistent, reads observe latest writes on the happens-before edge. | HB consistent, reads observe the initial values. |

|

|

| HB consistent, it is racy read. There is not happens-before edge between write on x and read on x. It is read via race. HB allows observing "unsynchronized" writes via race. | HB incosistent. We cannot use this particular execution to reason about program outcomes. This outcome is impossible. |

As expected the outcome r1 = 1, r2 = 0 is not possible in Java when y is volatile variable.

Store Buffering

Can this program see the following result r1 = 0, r2 = 0?

| Thread I | Thread II |

|---|---|

|

|

|

- On sequentially consistent hardware: no - On x86-TSO: yes - On ARM: yes - Java language (plain): yes - Java language (volatile x and y): no |

|

On sequentially consistent hardware, this outcome isn’t possible because instructions are executed in total store order. However, on x86-TSO, the outcome is possible because the write buffer from a processor may not have been flushed to shared memory.

Due to the reordering of instructions, it’s also possible to achieve the outcome in both ARM and Java programming languages (using plain variables).

By making both variables x and y volatile, the above outcome is not possible. There exists a happens-before edge between the write and read operations on both volatile variables, so one of the writes should be the first to be executed. Remember that reordering of instructions is not allowed across synchronization operations.

Load Buffering

Can this program see the following result r1 = 1, r2 = 1?

| Thread I | Thread II |

|---|---|

|

|

|

- On sequentially consistent hardware: no - On x86-TSO: no - On ARM: yes - Java language (plain): yes - Java language (volatile x or y): no |

|

This outcome isn’t possible in sequentially consistent and x86-TSO modes because the instructions cannot be reordered.

On an ARM model and with Java using plain variables, the outcome is possible because reads can be delayed until after writes.

In Java, declaring one of the variables as volatile, the above outcome is not possible. Any write operation on a volatile variable creates a happens-before edge, which prevents the compiler from reordering the instructions.

Coherence

Can this program see the following result r1 = 1, r2 = 2, r3 = 2, r4 = 1?

| Thread I | Thread II | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Thread III | Thread IV | ||

|

|

||

|

- On sequentially consistent hardware: no - On x86-TSO: no - On ARM: no - Java language (plain): yes - Java language (volatile x): no |

|||

Here is something that is not possible in the ARM model. This test checks if updates to a single memory location are observed in a different order.

The threads agree on the total order of writes to a single memory location. One of the writes overwrites the other, and all the hardware models agree on the order.

However, due to optimizing compilers, the read instructions on thread IV could potentially be reordered. While this is possible in Java with regular variables, it is not feasible with volatile variables.

Independent Reads of Independent Writes (IRIW)

Can this program see the following result r1 = 1, r2 = 0, r3 = 1, r4 = 0?

| Thread I | Thread II | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Thread III | Thread IV | ||

|

|

||

|

- On sequentially consistent hardware: no - On x86-TSO: no - On ARM: yes - Java language (plain): yes - Java language (volatile x and y): no |

|||

This is similar to the coherence test, but with two distinct memory locations. Primarily, we’re verifying whether threads III and IV observe the updates on x and y in different orders.

On ARM, there is no total store order guarantee on different writes. Similarly, the optimizing compiler could reorder the r3 and r4 reads, making thread interleaving to produce the above outcome.

Adding volatile to both variables, the outcome isn’t possible since it creates a happens-before edge that prevents the compiler from reordering the reads.

JCStress Tests

All of the litmus tests are validated using the JCStress framework. You can find the GitHub repository here at github.com/morazow/jmm-litmus-tests.

Locks

Java locks also provide the ordering, as lock enter happens before lock exit, which is similar to the behavior of volatile write and read. However, they ensure mutual exclusion, preventing two threads from concurrently accessing the locked or synchronized section.

Conclusion

With blog I tried to summarize my understanding of the Java Memory Model.

- We began by learning about the guarantees offered by the hardware models.

- We learned that by using proper synchronization mechanisms to ensure data-race-free implementations, the program outcomes could be explained as though they are executed in sequentially consistent manner.

- We looked into the Java Memory Model and learned how happens-before edges are established.

- We also ran several litmus tests to better understand how different models behave.

Acknowledgements

I could not have understood this topic without the help of the following resources.